Behind every artist, writer, and dreamer lies a terrain of choices, risks, and discoveries that can’t be plotted in advance. To create is to wander into the unknown, guided less by certainty than by curiosity. Each guest is asked the same ten questions, but their answers reveal something far greater—an unfiltered glimpse into the raw, unpredictable, and deeply personal terrain of a creative life.

Created by Connor Wolfe (they/them), founder of Wayfarer Books and Wayfarer Magazine, “Uncharted” is an invitation to step off the map and explore what it means to live, work, and create beyond the expected.

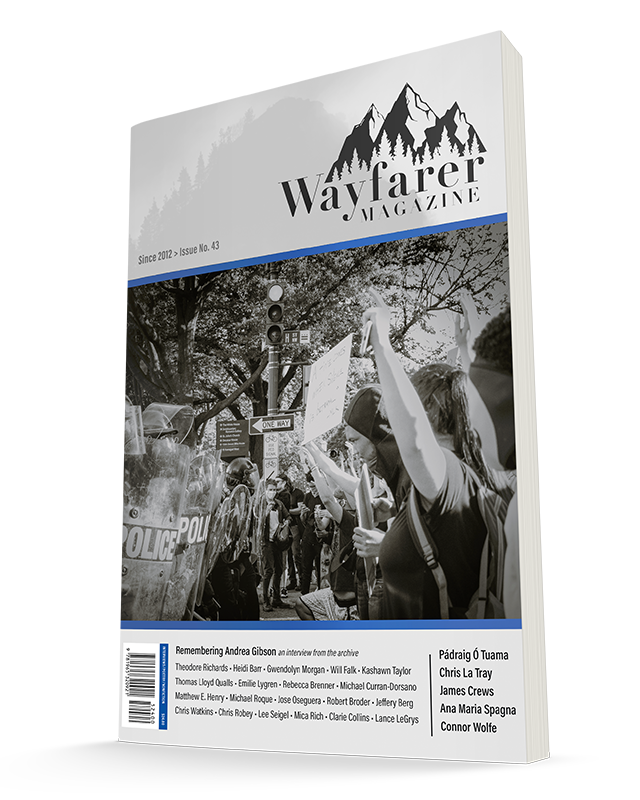

*This interview as featured in Wayfarer Magazine Print Issue 43

On Presence, Rebellion, and the Maps of Creativity

Today we’re joined by poet and theologian Pádraig Ó Tuama (he/him), whose work explores the intersections of language, power, conflict, and religion. He’s not only a gifted writer on the page, but also a compelling speaker, teacher, and facilitator of groups. Many will know him as the host of Poetry Unbound from On Being Studios.

From 2014 to 2019, Pádraig led the Corrymeela Community—Ireland’s oldest peace and reconciliation organization. His academic background is equally rich: he holds undergraduate and postgraduate degrees in theology, professional qualifications in conflict mediation, and a PhD in Poetry and Theology from the University of Glasgow. Looking ahead, he’ll be serving as a visiting scholar at Columbia University’s Centre for Cooperation and Conflict Resolution through the autumn terms of 2024 to 2028.

To give you a sense of his impact, BBC journalist William Crawley once introduced him at a TEDx talk by saying, “He’s probably the best public speaker I know.” And as The New Yorker’s Eliza Griswold observed, for Pádraig, “Poetry is the language the heart speaks not when it reaches for some externalized divinity but when it seeks to understand itself.”

1. What’s lighting you up creatively right now?

At this very moment, I am looking out at a tree, and in the tree is a bird. I’m traveling, so I’m around birdlife I don’t recognize. The bird has a yellow beak, and is sitting on a cluster of berries protruding from a tall slender palm tree. The berries are red and the bird’s plucking them off one by one, eating some, spitting others out, shitting merrily as it goes. Now it’s hopped to a twig so light, I can barely believe it can sustain the weight of even a light bird. And now—just seconds later—its flown to a large horizontal palm frond extending perpendicularly from a more sturdy tree. Somewhere else another bird is singing. In fact, I can hear three: something dove-like, something like a song, and something throaty and husky. Interestingly, I can’t hear the jungle fowl who—at any point of the day—can release their explosions of noise without warning. I’ve just counted, and in the space of five seconds, I could count ten different shapes of leaves and foliage on the immediate plants and trees and palms near me. And now, as if I’ve summoned them by writing about them, one of those damned fowl has crowed. I was awake early this morning, 4.15am or so, and the crowing started then, and it’s now six hours later, and it’s still pandemoniuming its way through the waking hours. The male jungle fowl has a slightly shorter crow than that of the domestic rooster—rising with objection, but without the elongated end. Right now, another bird—hidden too, and utterly new to me—is squeaking near me. It goes from a whistle to a nasal squeak, then back again. Fresh as the morning.

2. What’s the last thing that truly captivated you—an idea, a place, a piece of art, a poem, a moment?

The last thing? That bird. And the garden. And the light on the mountain last night when the sun was going down. I’m on Maui, staying in the house that Paula and W.S. Merwin built and lived in for many years. It’s run now by the Merwin Conservancy, a living land modeled after poetry, place, preservation. They— fools!— invite writers to stay for a few weeks while working on a project. (I’ve threatened to never leave). Merwin had purchased two acres about fifty years ago, with plans to build a house and plant on what was deemed wasteland. It’s now a rainforest of palm trees—some of them endangered—and birdlife and insect life (the little bastards love my milky blood, it seems).

3. What’s a recent experience that made you feel deeply present?

It started to rain last evening and continued all night. When I got up this morning, I made tea (Assam, with milk, in a flask to keep it warm) and sat on the lanai nearest to what was Paula Merwin’s office. I closed my eyes, listened to the rain, tried to recall what I’d read of the Stoics yesterday, and thought about the cardinal virtues (justice, wisdom, courage and moderation), but alongside that, I thought of the etymology of cardinal (it does not, as I’d wondered, share etymology with cardiac) and then—how could I not?—I thought of the cardinals I’ve seen flying around the trees during the week since I’ve arrived. The sound of the rain was like a permanent rhyme, a percussion, without metrical beat, but with a pulse as indigenous as that of the heart. And then I thought of how the Stoics were mostly interested in ways of being present, without allowing flights of uncontrollable things to take control. They didn’t think they were the first to state their wisdom: their wisdom has found voice in all human cultures, I imagine. My grandmother—in the midst of a long life with sorrow—loved the occasion for a song, or a cigarette, or a baby’s smile. And there were plenty. Babies that is. I’ve just counted: I was one of eighteen cousins born in eighteen years. She was present this morning too, although she’s never been to Hawai’i, and is dead many years. She was wearing the patterned housecoat she always wore, pottering about, uninterested in me, setting the butter out to soften in the warm.

4. What’s a piece of art, a book, or a conversation that’s been living in your mind rent-free?

I’ve been captivated by “Water” — Haleh Liza Gafori’s most recent translation of Rumi’s work (NYRB, 2025). I don’t believe in God (believe isn’t a strong enough verb for me), but I like reading some of the writing of some people who do. Linguist, musician, performer, communicator, seeker, Haleh is like conduit for the energies that also enlivened Rumi and, through her translations, I can see him: dancing, looking, calling out, whispering, shouting, spinning spinning spinning, praising his friend Shams, honoring Allah with his shouts of joy and lamentations, attending to life and the body and law and struggle with his full attention. A mynah bird has just landed on a branch nearby me. Mimics, they translate too: finding the part of their throats where the sounds they’ve heard can live through them. This one has gone from ticks to roars to purrs to song in the space of a minute.

5. What’s the most rebellious thing you’ve ever done in your creative work?

Rebellious according to whom? I have dared many things: to speak about religion and sex and the body as a gay man who has been through reparative therapies and exorcisms. But my guess is that anyone who’d find such writing rebellious isn’t interested in hearing what I have to say (if they’re even thinking of me; and I suspect they are not). So any rebellions in my creativity were mostly about my own relationship to my own relationship to my self… which, when you put it like that, appears just for what it is: centered on my self. The relationship to self is always going to be a serious relationship, but I hope, like the relationship to whatever God might be, I can look more through that connection, than at. I imagine any audience to my work is also looking at their lives, even anybody who reads my work and doesn’t agree with what I do with religion. But their lives are far more interesting than their opinions about me, and I want my imagination of their lives to be one of curiosity, not certitude. I suppose all of this is a way to say that art is more interesting than rebellion. I wrote a sequence of poems where Jesus, Son of God, fresh out of Hell, has a deep dialogue—erotic, frenetic, enraged, centering—with Persephone, queen of destruction, the Daughter of Gods. Someone suggested to me and said I had missed an opportunity for queering Jesus and giving him a male lover (Hermes? Hades? Apollo?).

I could vaguely see what they meant, but art rarely follows a line of a plot: for me, writing an encounter between these two devastated gods was imagination enough. Rebellion for rebellion’s sake doesn’t interest me any more. I’m interested in imagination and seeing where it takes me.

6. If your younger self could see you now, what would surprise them the most? What would disappoint them?

I think about my younger self a lot, but less in terms of surprise or disappointment. Mostly the energy goes back the other way: I have respect for the child and young man who felt like he had no map. He didn’t know the way, and to tell anyone about his secrets would have been to make life more difficult. He made it, anyway, or in some kind of way. Bruised, battered, slow. Self confident, strange, self destructive. Making art that knew more than he knew. Filled with self-consciousness, but also with an ambition. The cardinal is back. Maybe it’s not a cardinal—its coloring is more varied: butter yellow beak; black around its eyes; red feathers on its underbelly; purple wings. Lively. Sprite. Is it some kind of parrot? Is it a god? Oh the glory of this bird. I have no internet or mobile signal here, and my phone isn’t by me anyway, so I am without the ability to record or snap or look for information. The longer I look at it, the less interested I am in its definition anyway: what would information give me other than information? What I have is now, and I cannot stop looking at this bird, who has no interest in me. Perhaps that’s what would surprise the younger me: that I’d learn to be unafraid. What would disappoint the younger me? That it would take so much time. What would intrigue the younger me? That it took so much time. There was a green gecko here just five seconds ago. Gone now. I love those little lizards.

7. What is a truth you’ve had to unlearn in order to grow?

Fear. God.

8. What question are you currently trying to answer through your work?

Last night, I was invited by a new friend on Maui, Li, to go to an event in the home of Mary Anna and Steve Grimes, a night of music. I got the impression that many of the musicians there were friends or acquaintances; many of them had clearly known and loved each other for decades. They had stories of adversities overcome, wounds worn and borne, griefs marked. Moana and Keola Beamer played and sang, Keola on the guitar, and Moana singing and summoning up the ancestors by usage of the poi ball, as well as dancing hula while the singing was ongoing. What I am thinking of is not just the richness of their offering, it is also the way both of them could bear the beauty of their offering. It isn’t easy to share something so exquisite and not interrupt it with yourself, but they made a communion between listener and singer; singer and listener. Something happened in the space between. Not just between me and them, but between me and me: between me and my past and changing present; between joy and lament; between the dead and the living. I am not seeking any answers in the phenomenon of art; I am trying to be in the event.

9. What is pulling you forward right now?

I am interested in being drawn inward rather than forward. Time works in many ways, and one of the ways to thrive is to find a way to accept that time is going forward as well as make the time for some kind of travel inward; even if the idea of making time is a fiction, it can—like all fiction—do interesting work in us. My friend Jayne is here for some of the time at the Merwin Conservancy. She’s an artist and art therapist, and has spent the mornings collecting leaves and flowers from the pathways of the palm forest. She’s pressed them into paper and has made a small book of the shapes. I have another old friend with me too, Meister Eckhart. He died about 700 years ago, and wrote around 100 sermons. One of my favorite lines is where he notices fresh flowers on a grave at a convent. He mentions it in his sermon, praising the sister who made the arrangement of flowers, and commemorated the dead in the days of the living. He thought the human person lived on the hinge point between time and eternity: our days bring us through time, our prayers link us to eternity. Friendships—of all kinds—link me to time.

10. If your creative work is a map, where does it lead?

Maps interest me. They are a way to locate oneself today with the experiences—and point of view—of someone who either went that way before, or proposed some vantage point to make plot lines. I love the Czech poet Miroslav Holub’s gorgeous poem “A Brief Reflection on Maps” where a battalion of soldiers, lost in a blizzard in the Alps, found a map and made their treacherous way home. However, the map was not of the Alps, it was of the Pyrenees. If my creative work were a map, it would always lead off it. But it’s not a map. It’s a strange kind of mine; where to go downward is a way of attending to being present and being lost. The poet David Wagoner said in his magnificent poem “Lost”

“The trees ahead and bushes beside you

are not lost. Wherever you are is called Here

and you must treat it as a powerful stranger.”

Among the many pieces of wisdom present in this gorgeous poem that strike today are David’s choice of the words “ahead” and “beside” in the first line. One is looking forward, one is just adjacent. His poem is interested in neither of these orientations, but—as far as is possible—in the strange event of the here and now.

The cardinal is back again. On a sturdy twig of a small shrub-like tree. It’s peering down, chirping, perhaps looking for something to eat: a worm? a berry?

It’s raining lightly, I only see it when I look at the spaces between the trunks closely. And there’s a wind through the palm forest that reminds me why in many languages a name for breath is a name for God which is also the sound of what we cannot see. There’s sunshine also, glinting on the cartilage of the cardinal’s beak. The bird is hungry—or, at least, is seeking something that will sustain it on the edge of living. Me too.

Ahead and beside, Padraig O Tuama is always right t(here). 💫Sometimes seems like everywhere...

“ .. for breath is a name for God, which is also the sound of what we cannot see.”. I love this. Everything breathes. Everything has God in it. I can listen.