UNCHARTED: Rebecca Brenner

No map. No limits. Just the journey. An interview series with artists, writers, and disrupters by Connor Wolfe

Welcome to Uncharted: No map. No limits. Just the journey.

I’m Connor Wolfe, Founder of Wayfarer Books and Wayfarer Magazine, and I created this series around one simple question: What does it really mean to forge your own path? Each guest is asked the same ten questions—but the answers open a window into the raw, unpredictable, and deeply personal terrain of a creative life.

Today we are sitting down with Rebecca Brenner, an accomplished author, mindfulness meditation teacher, and journalist whose work spans a wide range of topics, from mental health and community care to equality and resilience. Her writing has been featured in publications including TIME, LA Times, Tin House, and Mutha Magazine. She also contributes as a journalist and features writer for TownLift, focusing on stories that reflect the vibrant Park City community.

As the president and co-founder of Mindful. Summit County, Rebecca works to advance mindfulness from an individual practice of self-care into a broader framework of community care. Under her leadership, the nonprofit aims to make mindfulness accessible and impactful, fostering a more connected and compassionate community. Her passion for advocacy also extends to her role as an elected member of the Leadership Team at Summit Pride, where she collaborates with city, county, and state leaders to promote equality and safety for queer communities in Summit County.

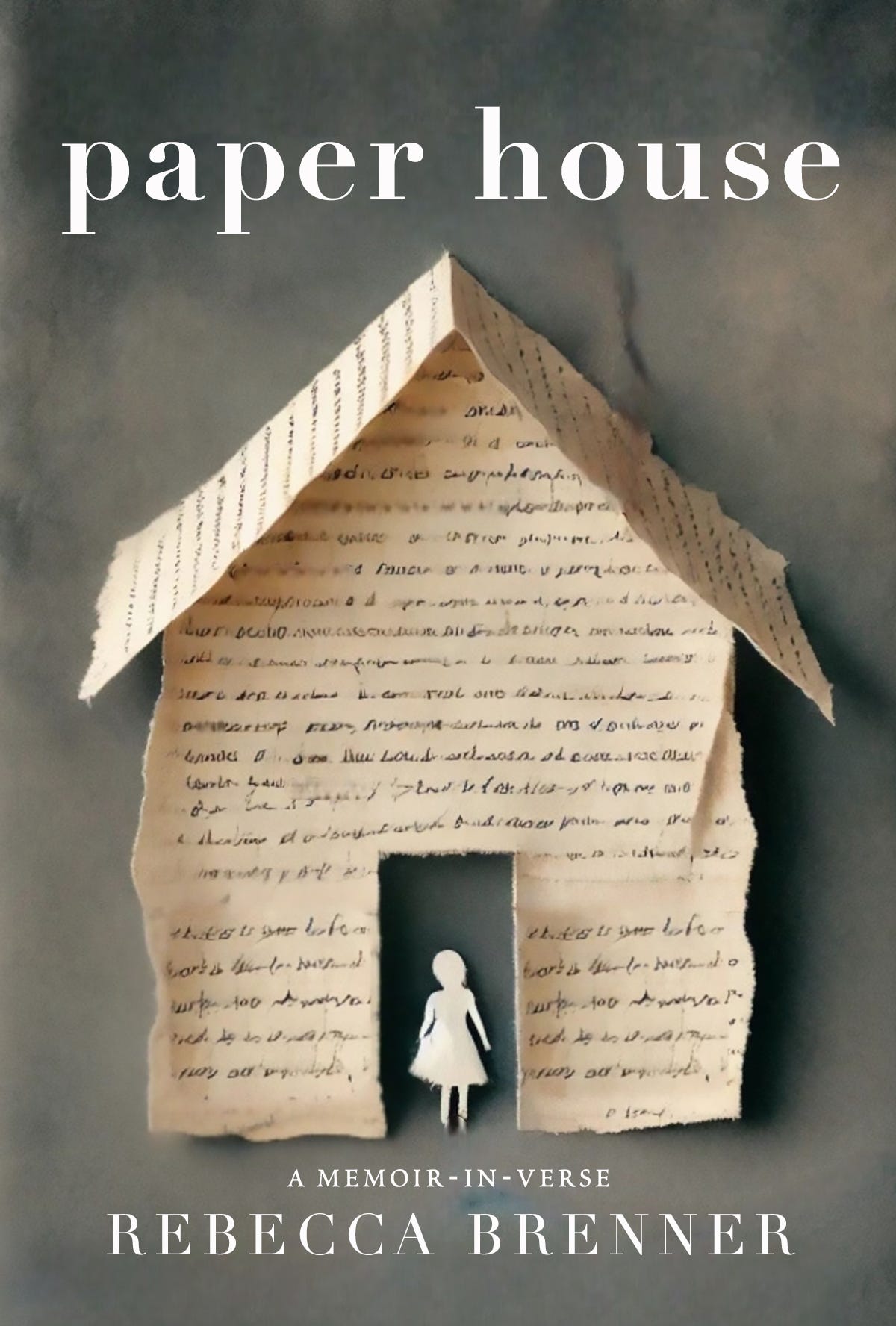

Rebecca’s creative work reflects her deep understanding of the complexities of human experience. Her debut memoir-in-verse, Paper House, explores themes of grief, addiction, and the intergenerational effects of loss, offering a poignant reflection on resilience and healing. The memoir, a deeply personal project over a decade in the making, is being released June 25, 2025.

Q: What's lighting you up creatively right now?

Right now, the pull to focus outward—on the news, on social media, on the constant flood of information—is strong. It’s hard to look away when so many of the people I love are having their rights stripped away, when injustice feels relentless, when the world demands urgency. There’s a part of me that wants to stay tethered to the noise, to stay in a state of constant reaction, as if my vigilance alone could shift the tide.

But I have learned that I am most nourished—creatively, emotionally, and spiritually—when I turn inward, when I settle into my body and the present moment. Rest is not complacency. Meditation, mindfulness, time in nature with my dog, Fred, and meaningful moments with family, friends, and my community don’t pull me away from what matters—they deepen my capacity to engage with it. These practices don’t silence my anger or grief; they give me the steadiness to hold them without drowning.

This connection to what is alive right here, right now, doesn’t just ground me—it sharpens me. It reminds me that presence is an act of resistance, that clarity is power. In a world that wants us exhausted, reactive, and overwhelmed, the ability to remain clear-headed, deeply rooted, and creatively engaged is radical. It allows me to move forward—not from a place of fear, but from a place of unwavering intention.

Q: What's the last thing that truly captivated you—an idea, a place, a piece of art, a poem, a moment?

For the past fifteen years, I’ve studied with a Lama from a Vajrayana Tantric lineage of Tibetan Buddhism. His teachings illuminated the fundamental life force energy—something vast and intelligent, alive yet groundless, endlessly creative. He often reminded me that life itself is inherently wise, that I could trust my own aliveness. At first, I struggled to grasp what that meant.

As someone who grew up in a home shaped by addiction and generational trauma, trust—especially in something unseen, something intangible—didn’t come easily. I had learned early on to be hyper-vigilant, to scan for signs of instability, to prepare for things to fall apart. Control felt like survival. The idea that I could relax into my own existence, that I could let go and still be held by something greater, felt almost impossible. It took years of practice, of unlearning, of testing the edges of surrender before I could even begin to trust what the Lama was pointing toward: that beneath all the chaos, beneath all the grasping, there is a current of life moving through everything—including me.

Recently, I’ve been slowly making my way through The Great Cosmic Mother: Rediscovering the Religion of the Earth by Monica Sjöö and Barbara Mor. When I read the words “Mother of God” and “Mother of Creation,” something deep within me shifted. I’m still searching for the right words to describe it, but it felt like an echo of something I already knew but had never fully allowed myself to believe.

It reminded me that aliveness is not just energy—it is loving, interconnected, and deeply creative. That it is central to who we all are, to who I am. That I can trust it. That my own aliveness is not something to control or contain but a source of interconnection, of power. And that perhaps, in all the ways I’ve been searching for solid ground, what I’ve really been searching for is this—the ability to rest in what is already moving through me.

Q: What's a recent experience that made you feel deeply present?

I'm so grateful for my fifteen-year practice because I can feel its momentum unfolding in my daily life, not just in meditation or intentional stillness, but in the most ordinary moments—where presence reveals itself as something vast and steady.

Take my morning walks with my dog, Fred. He moves through the world with such ease, with no agenda other than experiencing what is right in front of him—the scent on the wind, the crunch of snow beneath his paws, the rhythm of his breath. There is no rush, no worry, no analyzing what comes next. Just presence.

As I walk alongside him, the snow-covered trees, the mountains, and the way the morning light moves through the branches remind me that I, too, belong to this unfolding moment. They invite me out of the noise of my reactive, constantly chattering mind—the to-do lists, the anxieties, the endless internal dialogue pulling me elsewhere—and call me back into the simple, undeniable aliveness that is always here, always waiting.

These walks have become more than just routine; they are small rituals of returning—to myself, to the world as it is, to the steady rhythm beneath all the movement. In those moments, I remember that presence isn’t something I have to chase or force—it’s already here. I just have to notice.

Q: What's a piece of art, a book, or a conversation that's been living in your mind rent-free?

My poet friend, Nan Seymour, recently shared a poem by Nazim Hikmet, translated from the Turkish by Steve Kronen:

MY FUNERAL

Will my funeral start out from our courtyard?

How will you get me down from the third floor?

The coffin won't fit in the elevator,

and the stairs are awfully narrow.

Maybe there'll be sun knee-deep in the yard, and pigeons,

maybe snow filled with the cries of children,

maybe rain with its wet asphalt.

And the trash cans will stand in the courtyard as always.

If, as is the custom here, I'm put in the truck face open,

a pigeon might drop something on my forehead: it's good luck.

Band or no band, the children will come up to me—

they're curious about the dead.

Our kitchen window will watch me leave.

Our balcony will see me off with the wash on the line.

In this yard I was happier than you'll ever know.

Neighbors, I wish you all long lives.

It is a poem about death, yes, but somehow it feels more like a poem about life—about the simple, everyday details that shape a person’s existence. The narrow stairwell, the wash on the line, the trash cans standing as they always do. There is no grand farewell, no dramatic lament. Just a gentle acceptance, a quiet observation of the ordinary continuing on, even in death.

There is something deeply generous in this poem—its humor, its light touch, its absence of self-pity. Even in the face of finality, there is room for pigeons and children, for luck, for well wishes to those left behind. It does not ask for mourning, only recognition. In this yard I was happier than you’ll ever know. It is a line that settles into me like warmth.

The generosity and kindness in these words feel like a balm—an offering of perspective, a reminder that even in endings, there is a way to meet the world with grace, with humor, with love.

Q: What's the most rebellious thing you've ever done in your creative work?

My memoir-in-verse, Paper House, which will be published with Wayfarer this summer, is the most rebellious thing I’ve ever done creatively—not because it is loud or overtly defiant, but because it required me to go against everything I thought I knew about how this story should be told.

For years, my rational mind insisted it should be a traditional memoir, with neatly structured chapters and a clear arc. That’s how stories like this are written, right? That’s what the industry expects, what readers are used to, what would make it easier to publish. And yet, every time I sat down to write, it kept coming through in verse—fragments, images, white space, the silences just as important as the words themselves.

At first, I fought it. I tried to reshape it, force it into prose, make it more linear. But it resisted me. It wasn’t a traditional memoir, no matter how much I willed it to be. It was something else entirely—something raw, lyrical, woven in the language of memory rather than chronology. Some editors and agents encouraged me to reshape it, to make it more accessible by conforming to traditional storytelling. But the work refused. And, eventually, I had to surrender to what it wanted to be.

Trusting this form—trusting that poetry was the only way this story could live honestly—was terrifying at first. But in doing so, I learned something profound about creativity: it has its own intelligence. It is not something to be controlled, but something to be in conversation with. When I finally let go of how I thought the book should be written and instead allowed it to arrive as it wanted to, I felt something shift in me.

Writing Paper House in verse became an act of trust—not just in the work itself, but in my own instincts, in the intuitive and nonlinear nature of memory, in the idea that form and content are inseparable. And in the end, this trust deepened my belief in creativity as something alive, something wiser than my rational mind.

Q. If your younger self could see you now, what would surprise them the most? What would disappoint them?

My younger self would be shocked to learn that I am a parent and that parenting has been the most joyful, heart-breaking (in the best way), transformative, and healing experience of my life.

She would be disappointed that, despite always wanting a garden, I still can't grow one to save my life!

Q. What is a truth you've had to unlearn in order to grow?

There are so many lessons I’ve had to unlearn—like realizing that I don’t need to hurry through life or that I haven’t done something wrong each time I speak my truth. But the biggest one is control.

The Lama often said that all the Buddhist teachings could be boiled down to: “Relax and open. Relax and open some more. Relax and open even more.” For a long time, I assumed this meant that if I could just relax enough—if I could soften into the moment fully—I would finally arrive at a place of peace, clarity, and stability. That one day, I’d exhale and land somewhere solid.

But what I’ve come to realize is that there is no solid ground to stand on. Everything is always changing—my relationships, my work, my understanding of myself. There is no finish line where I get to say, There, now I’ve arrived. Instead, life keeps shifting, pulling me deeper into uncertainty. The difference now is that I don’t see this as something to fear or fix. Instead of resisting the unknown, I’m learning to trust it.

I don’t have much control—over outcomes, over how others perceive me, over what tomorrow will bring. But I do have the ability to meet each moment as it is, to relax into what is unfolding rather than gripping onto what I think should be happening. And in that surrender, I find something more lasting than control: an abiding trust in aliveness itself.

Q. What question are you currently trying to answer through your work?

What does it truly mean to live life in this way? This question lingers at the center of everything for me. It is not one that can be answered in a definitive way—there is no singular truth to land on, no endpoint where I can say, Ah, now I understand. Instead, it is a question that asks me to keep asking, to keep moving, to keep paying attention.

This question pulls me away from institutions and structures built on seeking certainty, order, and control—the things that promise stability but often come at the cost of fluidity and aliveness. I grew up believing that if I could just find the right system, the right framework, the right answers, I would finally feel safe. But what if the safety I’ve been searching for isn’t in certainty at all, but in the ability to stay present with the unknown?

So instead of asking how to make things solid, I ask: What does it mean for my work, my parenting, my relationships to remain in the unknown? To resist the pull toward rigid conclusions and instead stay in a space of curiosity, openness, and responsiveness? What does it mean to trust that I don’t have to have it all figured out in order to show up fully?

To live this way is to stay connected—to my body, to the breath, to the moment as it unfolds. It is to recognize that life is not something to grasp but something to be in relationship with. That aliveness is not a thing to be possessed or controlled, but a movement, an unfolding, a rhythm that I can choose to participate in.

It is both liberating and unsettling—to let go of the idea that I can shape things into certainty, to lean instead into what is emerging. But in doing so, I find something unexpected: a deeper sense of belonging, a deeper trust in the process itself.

Q. What is pulling you forward right now?

My two kids.

Every decision I make, every way I choose to show up in the world, is influenced by the quiet but undeniable pull of wanting to be here for them—for as long as I can, as fully as I can.

My mother died when she was only fifty-two. Her absence carved out an emptiness in my life that I’ve spent years learning how to live with. Now, as I approach the end of my forties, I am navigating aging without a map, moving through a stage of life I never got to witness her go through. There is no inherited blueprint, no guidance passed down from her on how to grow older, how to parent through different seasons, how to prepare for what’s ahead.

So I am crafting my own map.

I don’t take time for granted—not my time with my children, not my time in my own body. I want to live a long, healthy life, but not just in the sense of longevity. I want to age with an open heart and mind, to remain present and engaged, to continue evolving alongside my kids rather than simply watching from the sidelines. I want to be here not just as a parent but as a person who is still growing, still learning, still fully alive.

And more than anything, I want to see as much of their lives as possible—their triumphs and heartbreaks, their discoveries, the people they become. To walk beside them for as long as I can.

Q. If your creative work is a map, where does it lead?

Deeper and deeper into the here and now.

I hope my work guides me—and others—into each moment, fully awake and endlessly curious.

Connor Wolfe (they/them) is a writer, publisher, and advocate whose work spans over two decades and fourteen titles. Publishing from the margins of literary culture, Wolfe’s work has earned six Pushcart Prize nominations, the Gold Nautilus Medal for Poetry (2015), multiple Foreword Review Book Awards, and the Nautilus Silver Medal for Poetry (2022).

Wolfe is the founder of Wayfarer Books, an independent, trans-owned press committed to amplifying voices historically silenced by the mainstream. Their vision for literature as an act of resistance has shaped the press since its beginnings in 2011. Wolfe has served two terms on the Board of Directors for the Independent Book Publishers Association, delivered a TEDx Talk at Yale University, and completed a degree at Harvard University through grant programs.

After coming out as nonbinary and trans, Wolfe stepped further into national conversations around mental illness, erasure, and creative survival. Holding a degree in Psychology, they also studied Photojournalism under Samantha Appleton, former White House photographer for the Obama administration, sharpening their practice of bearing witness and telling the stories that often go unseen.

In 2024, Wolfe volunteered in the Collections Department of the Museum of Anthropology at Ghost Ranch, assisting in the preparation of sacred objects for repatriation under the revised Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act. After wintering off-grid in the high desert in the foothills of Pedernal, they are once again in motion, traveling with their three-legged black cat, momo, writing, documenting, and continuing the long walk home.