Our Angel of the Get Through / An Interview with Andrea Gibson by Connor Wolfe

From the Wayfarer Archive

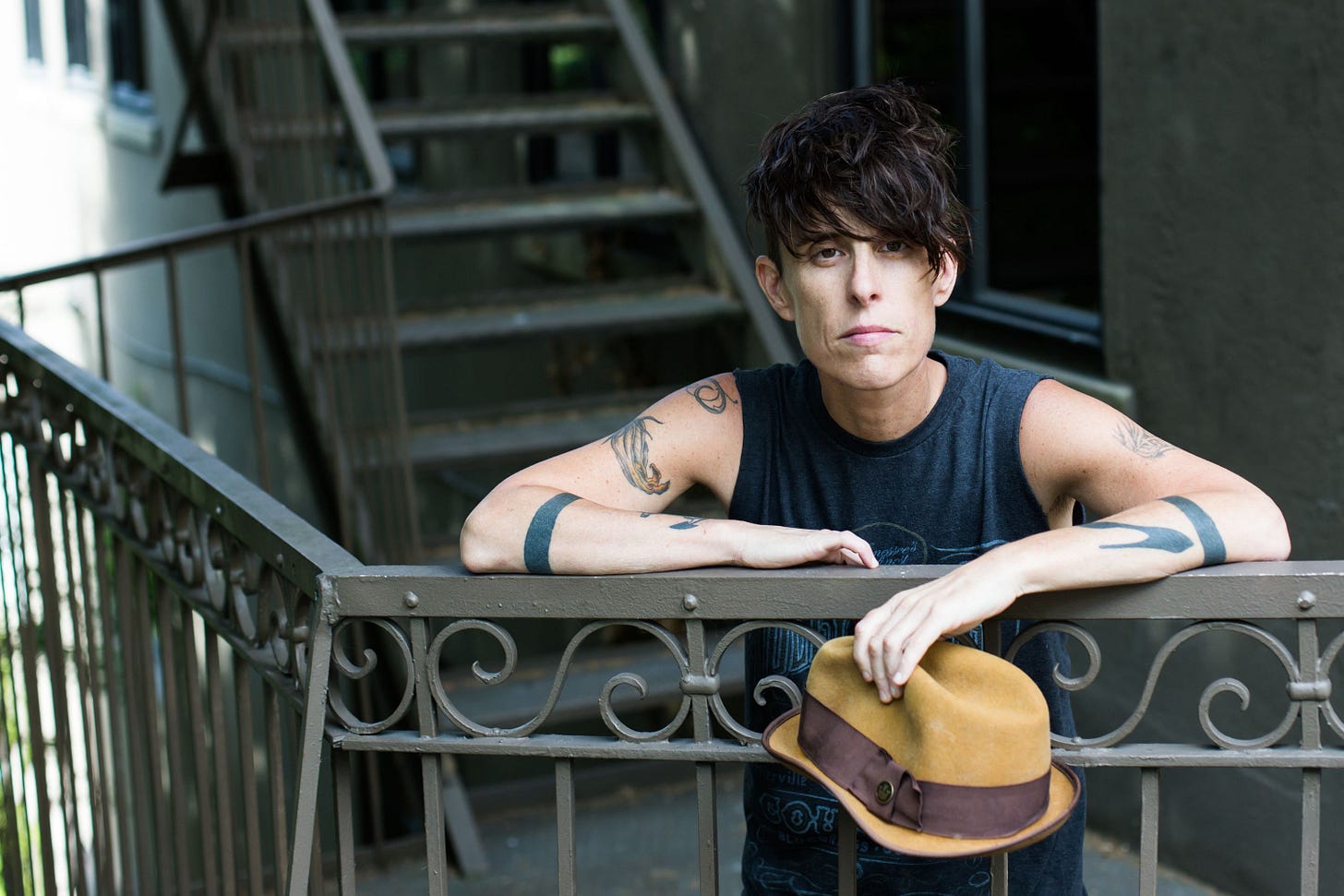

FROM THE WAYFARER ARCHIVE. 2017. // IN MEMORY OF ANDREA’S PASSING, JULY 14, 2025.

A Conversation with Andrea Gibson

I first saw Andrea Gibson (pronouns: they/them) perform during their Hey Galaxy tour at Babefest (a feminist-focused festival) in Provincetown, MA. The headliner was Ani DiFranco. I remember sitting in my seat in the intimate theater waiting for DiFranco to come out when I read that Andrea Gibson would be the opening voice. I remember thinking to myself how odd it was for a poet to be the opening act for a musician. As a poet myself, I don’t say this with judgment but rather with curiosity. When Andrea Gibson took the stage and began reciting their poetry, everything became clear. The poem recited: Orlando (touching on the Orlando shooting, which had happened only months before the evening in M.A.). There is little I can do to convey how powerful this poem is other than to say, in my humble opinion, that night the opening voice was even more captivating than the headliner, so instead I will simply encourage you to look up Gibson on YouTube, watch Orlando—and the rest of their videos—listen to it and then purchase it on iTunes so you can revisit it again. Gibson’s most notable accolades being Four-time Denver Grand Slam Champion and Women of the World Poetry Slam champion 2008. Born in Calais, Maine, Gibson has lived in Boulder Colorado since 1999. Their poetry and activism primarily center on gender norms, politics, social reform, and the struggles LGBTQIA+ people face in today’s society.

Connor: I’m going to dive right in . . . After seeing your first open-mic in Denver in 2000, you felt inspired to become a spoken word artist. What took place internally while you watched that open mic? What resonated so deeply with you?

Andrea: I attended my first open mic in Boulder, Co, and my first poetry slam a few weeks later in Denver. I had written throughout my life but had such overwhelming stage fright I never imagined I would ever willingly read my poems aloud in front of an audience. Looking back now I realize that much of what drew me to the stage was how afraid I was of it. Fortunately (ha!) for me that fear has hardly subsided in 19 years of performing. My experience of attending poetry events these days is not very different than it was in the beginning. I don’t know if it’s possible to faint from goosebumps, but I feel on the verge of that consistently when listening to spoken word.

Connor: In Lord of the Butterflies you write, “Your name is a gift, you can return if it doesn’t fit.” In addition to “Andrea,” you’ve also chosen the name “Andrew” and use gender-neutral pronouns, (specifically they/them/theirs). What were some of the mile-marker realizations along your process of defining yourself on the gender spectrum?

Andrea: I was in touch with my gender long before I came to terms with my sexuality, and long before I had language to define myself. As a child I very simply didn’t feel like a boy or a girl, and doubted I would ever grow up to feel like a woman or a man. In 2004 I heard the word “genderqueer” for the first time and immediately thought, “YES!” It wasn’t until quite a few years later though that I started asking my intimate community to use non-binary (they/them/theirs) pronouns for me, and a couple of years later I began using them publicly and writing more consistently about my own gender journey. In regards to my name—I don’t have much personal attachment to one, OR—maybe I just like having many names. Someone could ask 10 of my friends what they call me and there would be 10 different answers—Andrea, Andrew, Dre, Giba, Faye, Gib, Gibby, Sam, Andy, Pangee, Buttercup— yeah, I actually have a friend who calls me Buttercup. :)

Connor: Ha. That is amazing! We should all have that friend.

As someone who struggles with mental Illness, I see your own struggles with anxiety, depression, self-esteem, shame—all these inner-dynamics—run like veins throughout your body of work. As one who likewise struggles with depression, PTSD and shame, one the most-resonate lines for me is:

“I think the hardest people in the world to forgive are the people we once were.”

The unabashed authenticity with which you approach the pen unites all of us outliers, letting us know we are not alone. When did you decide that you were going to share those aspects of yourself? Was it a conscious choice to enter into this dialogue so wrought with taboo or were you simply being yourself?

Andrea: People create their safety in different ways. I have a few friends who feel most safe when what they are experiencing internally is something they process internally. I’m the opposite. The more I share about what’s happening in my emotional world, the more the tornado of my nervous system settles down. I don’t doubt that that has been, in many ways, a response to trauma—my historical desire to have a voice that is heard, but it’s one I feel good about honoring regardless. That said, as I’ve grown older, and have learned more and more to be the one who listens to myself, the one who shows up with softness when something deep inside of me starts screaming, I have less of a need to write to be heard as an individual, and more of a desire to show up creatively to a world harmed by silence. As you touch on above-- there is so much we have in common, and reminders that we are not alone can be life saving. Those reminders have certainly saved my life many many times.

Connor: When you recite a poem, your voice reverts with rhythmic, raging, raw rhymes. Each time you perform, you seem to not be reciting the poem but living it. When I gave a TED Talk on my own reality with mental illness, I felt like a streaker on stage—naked—only it was being recorded for posterity. The level of vulnerability was both terrifying and transcendent. Do you find it emotionally draining to give so much of yourself in every book, every performance? How do you refill yourself?

Andrea: I most often find writing and performing energizing. I feel more alive while doing both than I do at almost any other time in my life lately. But there are some poems and some topics that leave me feeling more naked than others. For example, I have chronic Lyme disease, and speaking to that on stage specifically is something that I can’t always do. When I started diving into the why of that I soon recognized that it’s, in large part, because of the tenderness of my audiences. I feel most vulnerable when I can feel people worrying about me and when I speak to my health (what I perceive as) worry sometimes permeates the room. It’s one of the places where I’ve been calling myself to be braver and to show up more courageously to my discomfort.

Connor: In “Angels of the Get-Through,” you write,

...I am already building the museum For every treasure you unearth in the rock bottom Holy vulnerable cliff God mason, heart heavier than all the bricks Say this is what the pain made of you An open open open road An avalanche of feel it all Don’t ever let anyone tell you, you are too much Or it has been too long...

Is your creative process an excavation of rock-bottom? ...Is it the alchemy of transcending this life’s pains into something of beauty? From what mental place do you usually take up the pen?

Andrea: When I look at my life I don’t see many absolute facts. Nor do I see many absolute truths. My life is what I call it and the more I have called it beautiful the more beautiful it has become. What I have called my biggest wounds have very often been my biggest blessings, because of where they led me, and because of how often they further opened my heart. I don’t want to say any of this flippantly and without respect for how real this hurting world’s walls are in relation to how possible it is to see the light in any given moment. But I have needed, for my own sanity, to find that light in every instant I possibly could, and that is most often where I write from, though it is not the only place. ...I’ll say one of the other primary places I speak from is rooted in the belief that even when the truth isn’t hopeful the telling of it is.

Connor: Have you ever written a poem that you were afraid to share? ...have you ever said to yourself, no, this is too intimate; I don’t think I can share this one?

Andrea: Yes. But there was a “yet” on the end of the sentence. “I don’t think I can share this one yet.” And hopefully soon, I will.

Connor: Finally, the first time I saw you perform was at Babefest in Provincetown. You opened for Ani DiFranco. I remember sitting in the audience awestruck as you performed “Orlando” –brought to tears as you kept going, verse by verse, striking the chords of my soul with each word. “...People outside pushing bandannas into bullet wounds. It’s true, what they say about the gays being so fashionable. Their ghosts never go out of style. Even life, it’s like funeral practice. Half of us are already dead to our families before we die. Half of us on our knees trying to crawl into the family photo...”

What do you view the role of the poet/artist to be in the current political climate?

Andrea: To inspire an untamable sense of urgency in regards to active boot-laced compassion. To actively imagine a better world and to write it down so that others might imagine it as well. To destroy the myth of our collective powerlessness. To create beauty where there isn’t yet beauty. To remind people they are not alone. To un-war our relationships to each other and ourselves.

Connor Wolfe (they/them) is a writer, publisher, and advocate whose work spans over two decades and fourteen titles. Publishing from the margins of literary culture, Wolfe’s work has earned six Pushcart Prize nominations, the Gold Nautilus Medal for Poetry (2015), multiple Foreword Review Book Awards, and the Nautilus Silver Medal for Poetry (2022).

Wolfe is the founder of Wayfarer Books, an independent, trans-owned press committed to amplifying voices historically silenced by the mainstream. Their vision for literature as an act of resistance has shaped the press since its beginnings in 2011. Wolfe has served two terms on the Board of Directors for the Independent Book Publishers Association, delivered a TEDx Talk at Yale University, and completed a degree at Harvard University through grant programs.

After coming out as nonbinary and trans, Wolfe stepped further into national conversations around mental illness, erasure, and creative survival. Holding a degree in Psychology, they also studied Photojournalism under Samantha Appleton, former White House photographer for the Obama administration, sharpening their practice of bearing witness and telling the stories that often go unseen.

In 2024, Wolfe volunteered in the Collections Department of the Museum of Anthropology at Ghost Ranch, assisting in the preparation of sacred objects for repatriation under the revised Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act. After wintering off-grid in the high desert in the foothills of Pedernal, they are once again in motion, traveling with their three-legged black cat, momo, writing, documenting, and continuing the long walk home.

What a talent and what a great loss. This article first turned me on to them. Thanks for reposting.

I will so miss Andrea’s voice in the world. It was always a gift, but especially these last few years.

I read they died surrounded by their wife, 4 ex girlfriends, parents, friends, and dogs. So typical of our community.